Chapter 1: Understanding foreign interference and its challenges

Special Report on Foreign Interference in Canada's Democratic Processes and Institutions

Broadly speaking, foreign interference includes attempts to covertly influence, intimidate, manipulate, interfere, corrupt or discredit individuals, organizations and governments to further the interests of a foreign country. These activities, carried out by both state and non-state actors, are directed at Canadian entities both inside and outside of Canada, and directly threaten national security.

Foreign interference involves foreign states, or persons/entities operating on their behalf, attempting to covertly influence decisions, events or outcomes to better suit their strategic interests. In many cases, clandestine influence operations are meant to deceptively influence Government of Canada policies, officials or democratic processes in support of foreign political agendas. Footnote 16

13. In the context of democratic processes and institutions, foreign interference can be a single act or a series of activities or behaviours over a period of time, throughout which a foreign state conceals its efforts to influence decision-making. Footnote 17 States engage in foreign interference in pursuit of a number of objectives, ranging on a spectrum from strategic to tactical. Strategic objectives include building or maintaining a positive or uncritical view of the state and its activities in Canada, and creating a disincentive to criticize a state’s domestic policies or practices. Tactical objectives serve the strategic goal, such as impeding, blocking or altering Parliamentary studies, motions or law-making that the state perceives as detrimental to its interests, or instructing individuals to undermine or support the efforts or aspirations of ethnocultural groups within Canada.

14. As will be described in Chapter 3, foreign interference activities in Canada in the period under review were conducted predominantly through person-to-person interaction, which the Committee referred to in its previous report as “traditional” foreign interference. Footnote 18 Foreign actors seek to cultivate long-term relationships with Canadians who they believe may be useful in advancing their interests, with a view to having the Canadian act in favour of the foreign actor and against Canada’s interests.

15. In this respect, foreign interference should be understood as a long-term effort, akin to espionage, using inducements or threats. Both dynamics enable the manipulation of targets when required, for example, through requests for inappropriate or special favours. Inducement typically involves two steps. First, a foreign actor offers the influential Canadian money or other favours. This may include direct payments, cash, in-kind campaign contributions, investment in their region, all-expenses-paid trips to the foreign country, or promises of an employment opportunity or a paid position requiring little to no work after leaving public office. This is intended to build a sense of debt or reciprocity. Second, once the Canadian accepts the foreign government’s money or another favour, the foreign actor uses it as a “bargaining chip” to gain leverage over their target. Footnote 19

16. The process may go on for years, and may develop at a slow enough pace that allows some Canadian targets to avoid, at least for a while, having to confront head-on that they are engaged in or assisting foreign interference. Some influential Canadians may self-censor on issues considered by a foreign country to be contentious, while others may internalize foreign messages and align themselves with the positions of these countries. Others may take action in the interest of the foreign state regardless of Canada’s position, and may even act in ways detrimental to Canada’s interests. Footnote 20

17. Foreign actors also employ coercive techniques to discourage efforts to counter the foreign state’s interest. These include denying visas, ordering the withdrawal of community support through votes or funds, or threatening the livelihood or benefits of family members living in the foreign state.

18. Foreign interference activities are distinct from acceptable diplomatic advocacy and lobbying. The latter activities are known to the host state and occur through recognized channels to achieve specific policy outcomes or objectives. It is normal for foreign diplomats in Canada, for example, to reach out to elected officials across the political spectrum, to pressure policymakers, to use local media to promote their national interests or to engage with and support domestic organizations. Canadian diplomats do the same abroad, advocating for Canadian strategic interests, seeking out influential state actors, and supporting initiatives that a host country may not fully welcome, such as pro-democracy projects. Whether employed in Canada or in another country, these activities are overt, declared to the host state, and consistent with the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Foreign interference activities are not.

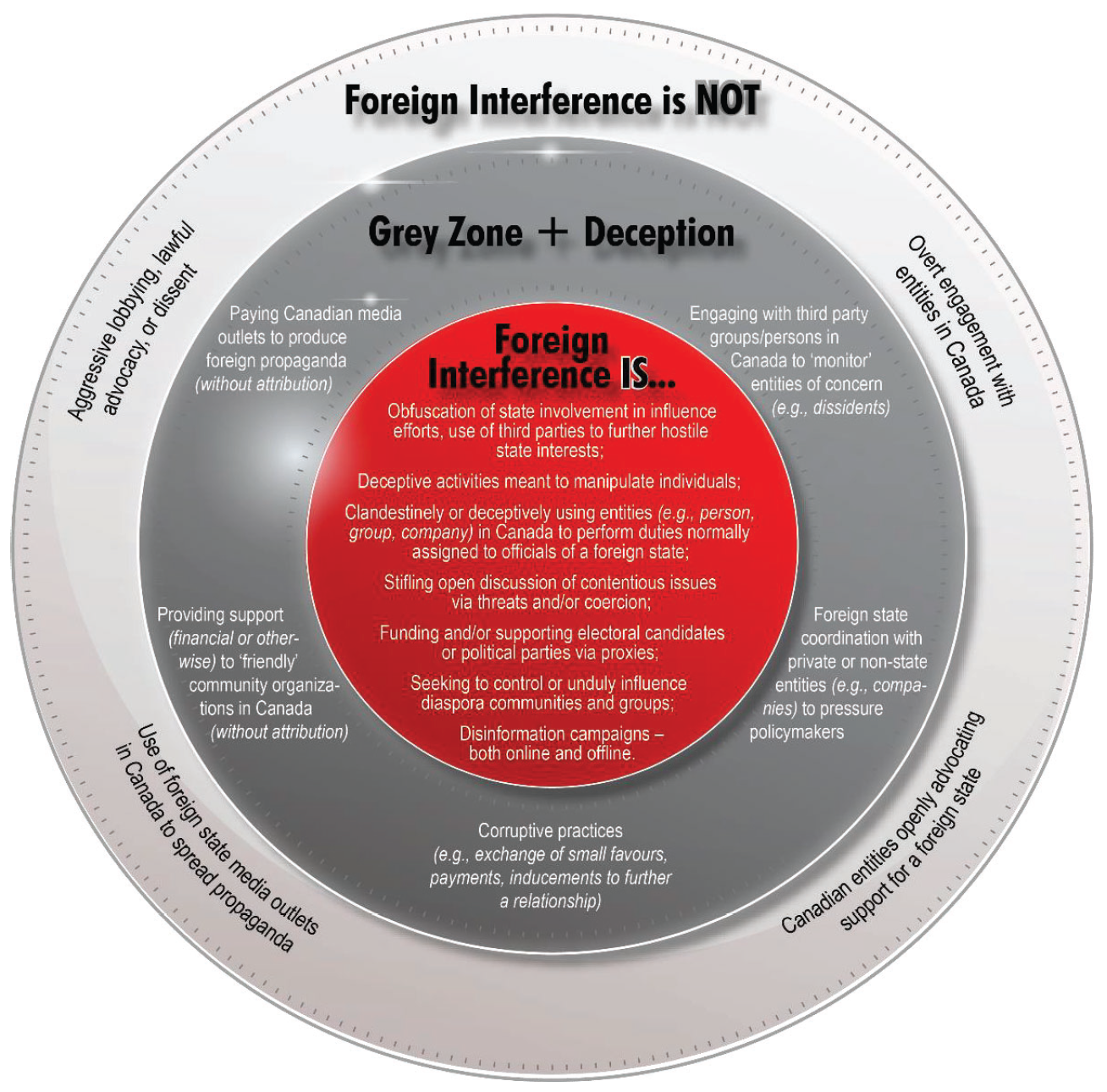

19. The Committee heard repeatedly from officials that identifying the line between foreign influence and foreign interference is not a straightforward exercise. Sophisticated foreign actors use a mix of both overt and covert activities. For this reason, significant amounts of foreign interference fall into a legal and normative “grey zone” (see Figure 1 below). Footnote 21 For example, it is not illegal for a foreign state to coordinate with a private or non-state entity to pressure policymakers. This activity becomes interference when the foreign state seeks to hide its involvement, direction or funding. Similarly, it is not illegal to pay Canadian media to produce coverage that portrays a foreign state in a positive light or to amplify the official policy of a foreign state. When that state conceals its involvement, however, this activity is no longer within the bounds of acceptable diplomacy and lobbying: it is foreign interference.

Figure 1 — Foreign Interference

Long description

Foreign Interference is not

- Aggressive lobbying, lawful advocacy, or dissent

- Overt engagement with entities in Canada

- Use of foreign state media outlets in Canada to spread propaganda

- Canadian entities openly advocating support for a foreign state

Grey Zone + Deception

- Paying Canadian media outlets to produce foreign propaganda (without attribution)

- Engaging with third party groups/persons in Canada to 'monitor' entities of concern (e.g., dissidents)

- Providing support (financial or other-wise) to 'friendly' community organizations in Canada (without attribution)

- Foreign state coordination with private or non-state entities (e.g., companies) to pressure policymakers

- Corruptive practices (e.g., exchange of small favours, payments, inducements to further a relationship)

Foreign Interference is…

- Obfuscation of state involvement in influence efforts, use of third parties to further hostile state interests;

- Deceptive activities meant to manipulate individuals;

- Clandestinely or deceptively using entities (e.g., person, group, company) in Canada to perform duties normally assigned to officials of a foreign state;

- Stifling open discussion of contentious issues via threats and/or coercion;

- Funding and/or supporting electoral candidates or political parties via proxies;

- Seeking to control or unduly influence diaspora communities and groups;

- Disinformation campaigns — both online and offline.

20. Another challenge is determining whether an activity is state-directed given efforts by the state to conceal its work. For this reason, it can be difficult to identify whether an individual is a target of foreign interference (e.g., unaware that a foreign state is acting on their behalf to support their candidacy), an unwilling accomplice (e.g., due to threats of sanctions), or a witting participant (e.g., knowingly taking direction from a foreign diplomatic mission). Footnote 22 Hostile states are aware of this grey zone and take advantage of it. Footnote 23

21. For example, a common tactic used to advance foreign interference is the use of proxies. A proxy is a Canadian or a person residing in Canada with a formalized relationship with the foreign state who wittingly and knowingly conducts activities on behalf of the foreign state’s interests. This tactic distances the threat activity from the foreign actor, giving the latter plausible deniability for their actions. A similar tactic uses co-optees. CSIS considers a co-optee as an individual who does not have a formal relationship with the foreign state, but is, to varying degrees of awareness, used by the state to further its interests. Footnote 24

22. Foreign interference activities ebb and flow according to foreign states’ strategic considerations. Historically, the shape and scope of foreign interference in Canada have been determined by factors such as a state actor’s ability and willingness to deploy resources for foreign interference activities; whether a state actor believes its actions will be met with meaningful consequences; and, whether a state’s homeland-related conflict has extended into Canada. Footnote 25 Foreign interference can also increase or decrease around major events: most notably for the purposes of this review, intensifying during election periods, which represent unique windows of opportunity for foreign actors to exert influence on all orders of government. Footnote 26 CSIS notes,

…for some foreign states, the decisions and policy stances of the federal, provincial, and municipal governments may negatively affect their core interests. As the world has become ever smaller and more competitive, foreign states seek to leverage all elements of state power to advance their national interests and position themselves in a rapidly evolving geopolitical environment. Footnote 27